The Mon people, also known as ဂကူမန် in Mon language, ဂကူမည် in Thai, and မွန်လူမျိုး in Burmese, inhabit various regions including Lower Myanmar’s Mon State, Kayin State, Kayah State, Tanintharyi Region, Bago Region, the Irrawaddy Delta, and several areas in Thailand, primarily in Pathum Thani province, Phra Pradaeng, and Nong Ya Plong. Their native language, Mon, is part of the Monic branch within the Austroasiatic language family and shares common roots with the Nyah Kur language spoken by a related group in Northeastern Thailand. Numerous languages in Mainland Southeast Asia have been influenced by Mon, and reciprocally, the Mon language has been shaped by these languages.

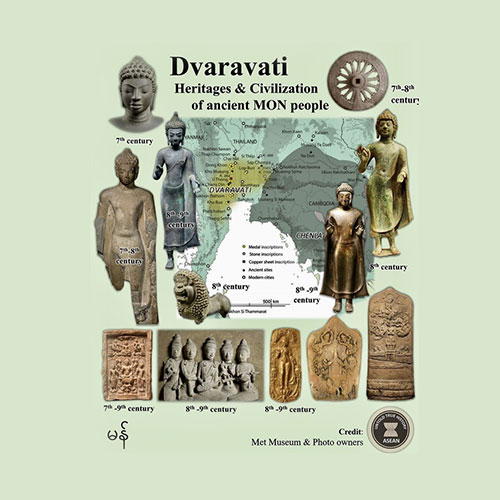

Historically, the Mon played a pivotal role in Southeast Asia, being among the earliest inhabitants and instrumental in spreading Theravada Buddhism in the region. The civilizations established by the Mon were some of the earliest in Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos, contributing significantly to the cultural landscape of Southeast Asia. Many present-day cities, including Yangon, Pathum Thani, and Vientiane, owe their foundations to the Mon people or Mon rulers.

In contemporary times, the Mon constitute a significant ethnic group in Myanmar and a smaller one in Thailand. Those in Myanmar are known as Burmese Mon or Myanmar Mon, while their counterparts in Thailand are referred to as Thai Raman or Thai Mon. The Mon dialects spoken in Thailand and Myanmar are mutually intelligible, highlighting the cultural and linguistic connections that persist among the Mon communities in different regions.

Ethnic Identification

Throughout history, the Mon people have been known by various names depending on the groups referring to them. In the pre-colonial era, the Burmese labeled them as Talaing (တလိုင်း), a term adopted by the British during the colonial period. Europeans also used the term “Peguan” when Pegu served as the capital of Lower Myanmar.

The term “Talaing” dates back to inscriptions from the 11th century but is now considered pejorative and is no longer in widespread use, except in specific historical contexts such as the eponymous song genre in the Mahagita, the collection of Burmese classical songs. The etymology of “Talaing” is a subject of debate, possibly derived from Mon or referencing Telinga or Kalinga, a geographic region in southeast India. By the 12th century, the term took on a derogatory meaning within the Mon community, becoming a disparaging label for the mixed offspring of Mon women and foreign men.

The term “Mon” (spelled မန် in Mon and မွန် in Burmese), synonymous with the Burmese word for ‘noble,’ likely originated from Old Mon “rmeñ,” passing through Middle Mon “rman” (ရာမန်). The ethnonym “rmeñ” first appeared in the Kyanzittha’s New Palace Inscription of AD 1102 in Myanmar. Derivatives of this ethnonym have been discovered in 6th to 10th-century Old Khmer and 11th-century Javanese inscriptions. King Dhammazedi coined the geographic term Rāmaññadesa in 1479, now referring to the Mon heartland on the Burmese coast.

In Myanmar, the Mon are categorized into three sub-groups based on their ancestral regions in Lower Myanmar: Mon Nya (မန်ည; /mòn ɲaˀ) from Pathein (the Irrawaddy Delta) in the west, Mon Tang (မန်ဒိုင်; /mòn tàŋ/) in Bago in the central region, and Mon Teh (မန်ဒ; /mòn tɛ̀ˀ/) at Mottama in the southeast.

Mon Tang

Mon Teh

Mon Nya